A Tamil Folklore

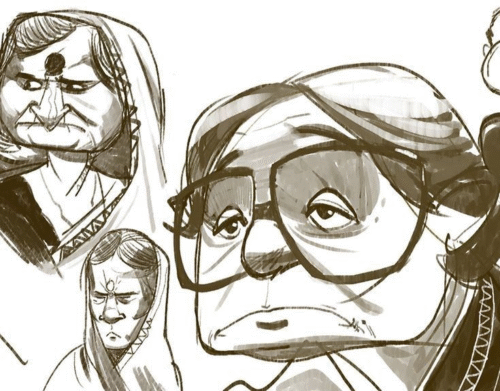

A poor widow lived with her two sons and two daughter-in-laws. All four of them scolded and ill-treated her all day. She had no one to whom she could turn and tell her woes. As she kept all her woes to herself, she grew fatter and fatter. Her sons and daughter-in-laws now mocked her for growing fatter too and started commenting on her eating.

One day, when everyone in the house had gone out somewhere, she wandered away from home in sheer misery and found herself walking outside town.

There she saw a deserted old house. It was in ruins and had no roof. She went in and suddenly felt lonelier and more miserable than ever; she felt she could not bear to keep her miseries to herself any longer. She had to tell someone.

She told all her tales of grievance against her first son to the wall in front of her. As she finished, the wall collapsed under the weight of her woes and crashed to the ground in a heap. He own body grew lighter as well.

Then she turned to the second wall and told it all her grievances against her first son’s wife. Down came that wall, and she grew lighter still. She brought down the third wall with her tales against her second son, and the remaining fourth wall, too, with her complaints against her second daughter-in-law.

Standing in the ruins, with bricks and rubble all around her, she felt lighter in mood and lighter in body as well. She looked at herself and found she had actually lost all the weight she had gained in her wretchedness.

Then she went home.

This story has a strong connection with a core thought of Indian metaphysics . According to it, material and non-material things are part of a continuum of “gross” (‘sthula’) and “subtle” (‘suksma’) substance. Thus transformations between subtle and gross is possible.

It is to be noted that the story does not talk about the woman’s cruel family being converted, becoming kinder. Only she goes through a change by expressing herself to the walls and getting unburdened of her sorrows.

Such a notion of catharsis is, probably, not to be found in Indian classical literature. But a folktale is weaved with real-life experiences of common people. So we find this folktale hinting at the fact that stories, particularly one’s own stories, have certain elements of catharsis inherent in them.

The story takes birth in India yet the main theme of the story reminds us of Freud’s concept of repression as a defense mechanism.

It hints towards the psycho-somatic implications of emotional knots and blockages that often form when we do not process our trauma. Those emotions often go into our unconscious and manifest themselves in various physical abnormalities. Sometimes a moment of catharsis brings them back into the conscious mind and releases the pent-up emotions.

The walls in the story are metaphors for shields that we often build around our most painful emotions and keep ourselves away from fully experiencing them.

Sometimes solitude and isolation can give one the freedom and courage to break that protective shield. And come to terms with the pain and anger residing in our unconscious.

Perhaps there is a cue in the story that the ultimate safe space is our own inner world. Inside this inner world, a child still resides who yearns to go back to innocence. It wants to shed off all pretensions and the burden of behaving like an adult. It wants to experience and express life with authenticity. It wants to cry and laugh with no judgments, no consequences.