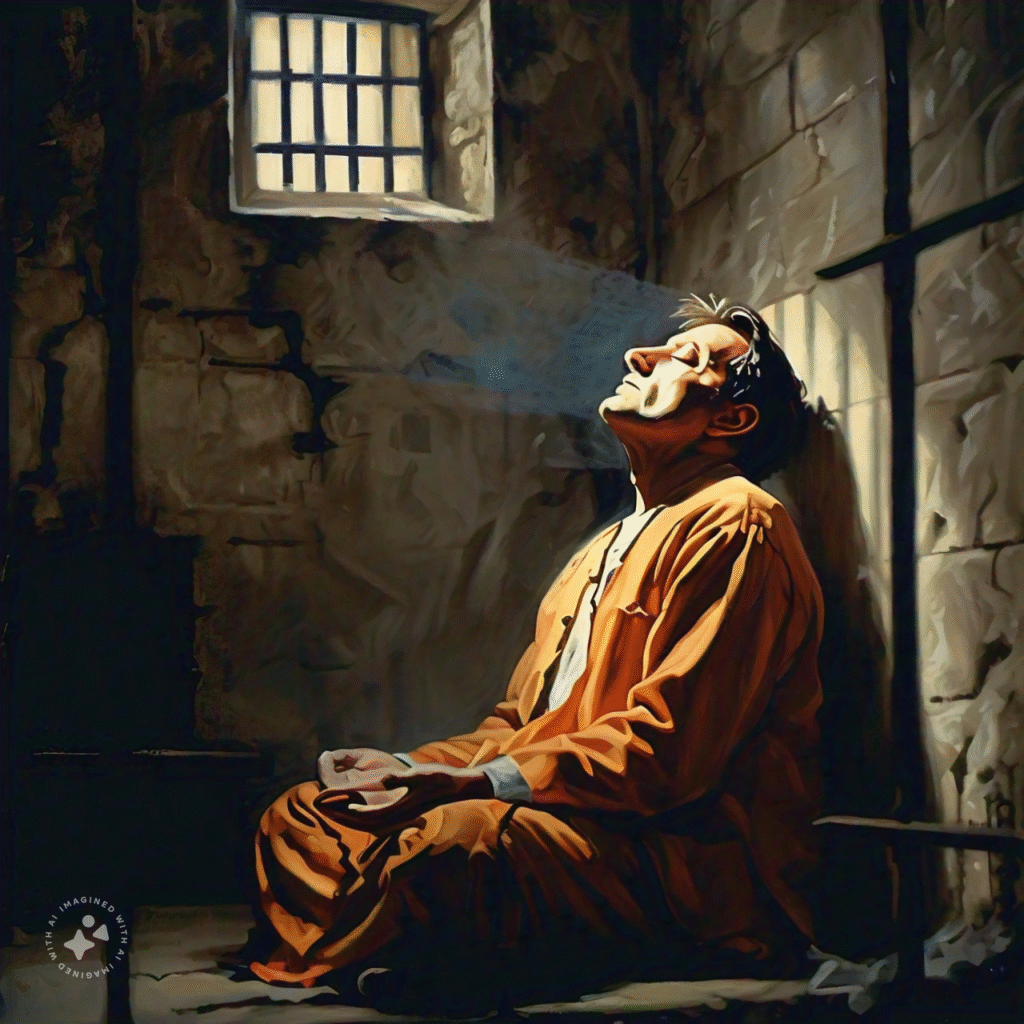

“It took me a long time and most of the world to learn what I know about love and fate and the choices we make, but the heart of it came to me in an instant, while I was chained to a wall and being tortured. I realised, somehow, through the screaming of my mind, that even in that shackled, bloody helplessness, I was still free: free to hate the men who were torturing me, or to forgive them. It doesn’t sound like much, I know. But in the flinch and bite of the chain, when it’s all you’ve got, that freedom is a universe of possibility. And the choice you make between hating and forgiving, can become the story of your life.”― Gregory David Roberts, Shantaram

We know that the beginning of many great narratives of freedom was in a prison. The intensification of inner life gives birth to a powerful transcendental energy of the soul and one’s limited perception of earthly existence opens up into the glorious expanse of a Universal Presence. The purpose of life is raised to a higher, nobler ideal.

Stories of prisoners and prison life have always remained inspiring for many who feel shackled by life-situations.

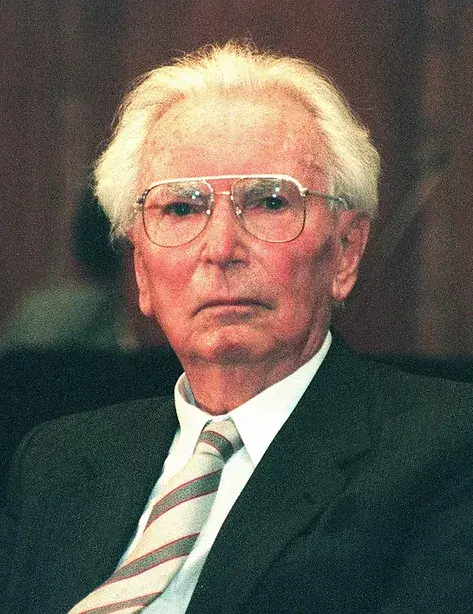

One such story is of Victor Frankl who was an Austrian neurologist, psychologist, philosopher, and Holocaust survivor. His experiences as a prisoner in Nazi concentration camps during World War II made him realize that:

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Frankl spent three years in four concentration camps and lost his newly-wedded wife, his parents and his brother. He chronicled his journey in his autobiographical book Man’s Search for Meaning.

He founded Logotherapy. It is a form of existential and humanistic therapy. While explaining the principle on which Logotherapy is based, he says that it:

focuses on the meaning of human existence as well as on man’s search for such a meaning. According to logotherapy, this striving to find a meaning in one’s life is the primary motivational force in man. That is why I speak of a will to meaning in contrast to the pleasure principle (or, as we could also term it, the will to pleasure) on which Freudian psychoanalysis is centered, as well as in contrast to the will to power on which Adlerian psychology, using the term “striving for superiority,” is focused.

During the therapy sessions with his clients, Frankl insisted on knowing one good reason for which they wanted to live and that used to be his starting point. Hence, in sharp contrast to Freud’s psychotherapy which was about dealing with past trauma, Victor Frankl’s logotherapy was about counting one’s blessings in life and strengthening one’s will to look at the future with hope.

Existential crisis is typical of modern societies in which people do what they are told to do, or what others do, rather than what they want to do. They often try to fill the gap between what is expected of them and what they want for themselves with economic power or physical pleasure, or by numbing their senses. It could lead to neuroses and manifest in the form of depression, anxiety, obsession, phobia, etc.

Instead of trying to find the reason behind the neuroses, Logotherapy insisted on focussing attention on discovering life’s purpose. The quest to fulfill one’s destiny then motivates one to press forward, breaking the mental chains of the past and overcoming whatever obstacles one encounters along the way.

Existential frustration arises when our life is without purpose, or when that purpose is skewed towards desire-driven narratives. In Frankl’s view, however, there is no need to see this frustration as an anomaly or a symptom of neurosis; instead, it can be a positive thing—a catalyst for change.

Logotherapy does not see this frustration as mental illness, the way other forms of therapy do, but rather as spiritual anguish—a natural and beneficial phenomenon that drives those who suffer from it to seek a cure, whether on their own or with the help of others, and in so doing to find greater satisfaction in life. It helps them change their own destiny.

In Frankl’s view, many of the patients who do not come with some congenital problems essentially do not have any problem . They are simply in search of a new life’s purpose and as soon as they found that out, their life took on deeper meaning.

Frankl had immense faith in man’s capacity to rise and grow beyond his biological, psychological or sociological conditions. He believed “Man is capable of changing the world for the better if possible, and of changing himself for the better if necessary.”

In Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl cites one of Nietzsche’s famous aphorisms: “He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how.”

Based on his own experience, Frankl believed that our health depends on that natural tension that comes from comparing what we’ve accomplished so far with what we’d like to achieve in the future. What we need, then, is not a peaceful existence, but a challenge we can strive to meet by applying all the skills at our disposal. It is about an individual’s free-willed progress. But this free-will is not arbitrary, rather it ought to come with a sense of “responsibleness”.

Frankl notes that there are generally two sides to any kind of neurosis – 1) ANTICIPATORY ANXIETY and 2) HYPER-INTENTION.

Anticipatory anxiety is a classic trait in neurosis. It is characteristic of this fear that it produces precisely that of which the patient is afraid. For example, if one is always afraid of stammering in public, then he/she will be more prone to stammering when speaking in public. Basically, fear brings about that one is afraid of.

Similarly hyper-intention makes it impossible to do what one wishes. Hyper-intention basically means excessive-thinking or paying too much attention to the outcome of an action. This leads to not being attentive to the action itself and not allowing the action itself to take its own course. One forcibly tries to get the desired outcome disrupting the natural flow of the action.The result could be jeopardizing the action and the outcome both. For example, if one intends to give a brilliant public speech and keeps excessively reflecting on it, chances are that he/she would end up being too self-conscious and not even give an average speech.

Logotherapy bases its technique in setting a “paradoxical intention”. It consists of a reversal of the patient’s attitude and his fear is replaced by an opposite wish. By this treatment, the wind is taken out of the sails of the anxiety. The patient is encouraged to find humour in his compulsive behaviour and to think on the lines that such a small error hardly has any meaning in the larger scheme of things in his life.

This leads to a part of one’s self being detached from the part which is “problematic”. Once there is some amount of detachment, there is some respite. The vicious cycle of unrestricted self-concern is ruptured to an extent.

Once this step is successfully done, the client is shown that the feeling of self-pity or self-contempt that he/she has been feeling arises from a deeper sense of emptiness. The desires that occupy his mind and body obsessively can be shaken away and the suffering can be taken away, only when life’s purpose is discovered. Ultimately we are not answerable to our small desires, rather we are answerable to Life. Life has given each of us a free-will. To not use it with full freedom and absolute responsibility, would be deceiving not just ourselves but Life itself.